Why I’ll wear Orange on Canada Day

June 18, 2021

On every Canada Day, I have worn Red as the colour of Celebration.

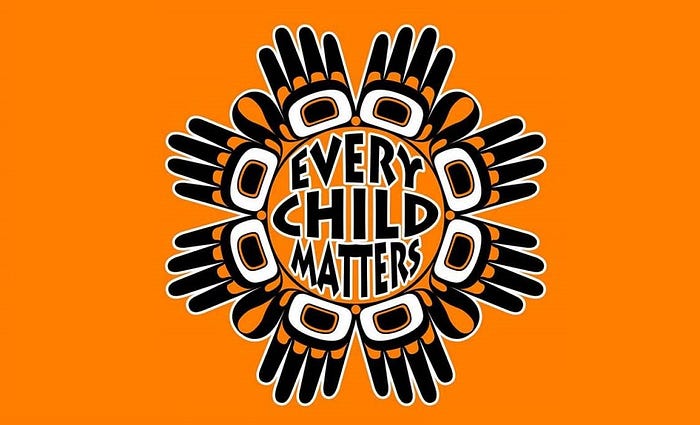

This year, I will wear Orange on the 1st of July.

Orange. The colour of Reflection and Remembrance, as we cope with long-buried Truth.

And I hope you will feel able to join me.

Officially, Orange Shirt Day is September 30 of this year, the first time that the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation officially becomes a statutory holiday.

Orange is the colour of Reconciliation in Canada.

Reconciliation with our country’s past.

Reconciliation, as a necessary foundation for our common future.

As I write, provincial governments are funding the search for mass graves on the sites that were once residential schools.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 2015 report on Canada’s colonial legacy foretold the mass gravesites.

Yet it took the unearthing of a mass grave in Kamloops three weeks ago to jolt our collective conscience.

I was saddened that so many of my fellow Canadians expressed surprise and shock.

Clearly, we as a people have not come to a full reckoning with our past.

So let’s make a start. Here’s why I hope you’ll think about wearing Orange on Canada Day.

Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan, April 2016

We are seated in a circle in a brick and stone building, some two dozen of us. The colonisers who came to Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan claimed there was such a thing as “owning” the land that kisemanito, the creator, gave us to share. They put this building here. They called it the Prince of Wales Armoury. They gave their young men guns and helmets, and sent them off by the thousands, from this very spot, to die on foreign shores. All to serve the delusion that people can “own” the Mother Earth which all are meant to share.

This is the circle in which we the people have met in Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan for more than 10,000 years, as the colonisers reckon time. This is where we are gathered today, newcomers and the descendants of the first people to live along this river and these hills, as the people of Treaty Six. This is the sacred agreement, sealed with a bundle, that enables first peoples and newcomers to share this land, to care for the land and water and sky — and for each other — as long as the sun shines and the rivers flow.

And today in this circle, we are coming to grips with the great wrong the colonisers wrought, the terror they visited on those who had shared Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan — Beaver Hills House, in the language in which the colonists govern — and what can be done to reconcile the future with the never-ending sin of what was done in the past. This is land once shared by the Cree and Dene, by the Lacotah and the Métis, the Siksika and the Pikani. Today it is dominated by newcomers. The colonisers who divided up “ownership” of this land named the territory after a princess from a faraway land across the sea. They called it Alberta.

The colonists came here for the pelts of the beavers after whom first peoples named this place. And their first leader, a Hudson’s Bay Company factor, gave Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan the name of the place he came from. Edmonton.

I have convened this circle, in my role as chair of the Edmonton Heritage Council. In the centre of the circle is a pile of books, a catalogue of pain, dripping with the unhealed wounds of those of our brothers and sisters who were plucked up by their roots, sent to state detention, forced to abandon everything that defined their being and belonging: names, languages, family, culture, heritage, spirit, and the absolute freedom to roam these lands.

This stack of books is the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission which travelled the country called Canada for six years, to understand the pain of the first peoples so brutally wrenched from all we have and are, and to find a path towards mutual healing. Beginning with the recognition of the wrongs committed in the never-ending sin.

We are listening to one of the Commissioners, Wilton Littlechild, as our circle evokes the paths to reconciliation the Edmonton Heritage Council can pursue. I knew Chief Littlechild during the many years he represented Maskwacis and surrounding coloniser communities: as a Progressive Conservative member of Parliament in the House of Commons of Canada; and as regional chief of Alberta, representing the people of Treaties Six, Seven and Eight in the Assembly of First Nations. He has agreed to come to this circle, to help we keepers of shared heritage navigate a new way of being and belonging together.

Canada is the name the colonisers applied to the entire land they claimed from sea to sea to sea, even though its origin, kanata, is the word for a pristine settlement on Turtle Island, in the language of the Haudenosaunee people who lived along the Kaniatarowanenneh, the great river-sea, which the first colonisers named le Saint-Laurent. These colonists called the people the Iroquois, but knew the Haudenosaunee comprised six distinct indigenous nations.

The mighty river did not change, nor did the people, as the English colonists who defeated the French ones called the river St. Lawrence, and named the people “savages.”

The official practice, among the English colonists, was to call all the people who lived on Turtle Island “Indians.” All because of a foolish explorer named Cristobal Colon (Christopher Columbus in English), who set sail from faraway Barcelona. Leading a flotilla of three sailing ships, Colon reached the cluster of southeastern islands off these shores in year 1492 of the Christian calendar — many millennia after the first people’s ancestors spread throughout these lands. Colon thought he had found the western route to the country his peers knew as India, thus the people he encountered must be “Indians.”

In fact the first people’s ancestors already had made contact with people from northern Europe called Viking, who left a settlement in the land of the Beothuk, the Mi’kmaq, and the Inuit five hundred years before Colon. Unlike Colon, they had no deranged notion that kisemanito’s bounty to the people actually belonged to anyone who could take “ownership” by violence.

Colon and the colonists who arrived with him claimed ownership of the land in the name of their king and queen. These monarchs were two genetically inbred individuals named Ferdinand and Isabella: who called themselves “their most Catholic Majesties” and believed that kisemanito was in fact incarnated as a bearded man nailed to a cross. And that this nailed god gave them the divine power to take “ownership” of any part of Turtle Island reached by their mariners and voyagers.

In the name of their god, the French colonisers led by Jacques Cartier, and Samuel de Champlain after him, took tracts of kisemanito’s land, and claimed all of it should be called New France. They were defeated in battles by English colonists. These English brought diseases which took the lives of many people who lived along the great river. And for those who survived, the fate of their descendants was even worse: to lose their very identity and being as their “government” snatched children away from their families, determined that there should be “no trace of the savage left” in any “Indian” once the prison-schools in which they confined the children had finished in their task of erasing who and what the children once were.

These are the stories of the traduced first people and their descendants, in the pile of books in the centre of our circle. Chief Littlechild’s voice is even, his tone restrained, as he continues to describe the indescribable. And insists we are here to find a path forward in the mutuality of being and belonging. His calmness is overwhelming, and for those of us who have read the report, the dignified timbre of his voice is unbearable. A shouted reproach would have been easier to understand; his demeanour merely emphasises the enormity of the sin unredeemed.

Pomona, California, USA, September 1964

My parents and I are invited to visit the suburban home of one of my father’s colleagues in the psychology department of the University of California at Los Angeles. We arrive in our family’s first car, a 1953 Oldsmobile, having driven from our apartment in Brentwood.

When we pull up, we find their children have climbed up the tree in the front yard, scampering up to the highest limbs that will bear their weight, trembling in terror.

They were told by their father that Indians are coming to their home.

Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan, April 2016

Wilton Littlechild, Grand Chief of the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations, speaks in our circle about the chronicles of injustice and grief in his commission’s report, takes measure of our burdened faces. He passes me the sacred object which entitles the bearer to speak in circle. My heart is so laden that no words come. I pass.

I understand why Chief Littlechild has spoken the way he has, how he has stayed so composed in describing the commission’s work: page after harrowing page, churning the emotions of all who learn the experiences captured in the testimony gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation researchers.

Describing another catalogue of brutality, the Second World War, whose terrors unfolded in a different continent at a different time, the Greek poet Yiorgos Seferis observed in The Last Stop:

Ki’ a sou mílo me paramýthia kai paravolés

eínai giatí to’ akoús glykótera, ki i friki

de kouventiázetai giatí eínai zontaní

giatí eínai amíliti kai prochoráei

Stásei ti méra stásei ston ýpno

mnisipímon pónos

Which in my rough-hewn translation becomes:

If I speak to you in myths and parables

it is gentler for you that way, because horror

really can’t be described, because it’s living

because it multiplies without speaking

a pain that wounds memory

drip by drip, by day by night

All the justifications used by the government of Canada: the need to “civilise” cultures they did not understand, to violently coerce “savages” into a “superior” culture, are echoed in modern China’s reasons for the mass detention and “re-education” of Uygur Muslims in Xinjiang since 2016. The difference is this: Canada had no intention, as China does, of bringing economic development and a higher standard of living to the first peoples. Nor did Canada face violent, armed resistance to their governance. Nearly all who were detained by Canada, with the aim to have their roots and their identity destroyed, were people of treaty who were promised mutually beneficial coexistence with the colonists and the newcomers.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission arose from the settlement the government of Canada reached in 2007 with the survivors of the residential schools. It was launched after a historic apology delivered in the House of Commons by Prime Minister Stephen Harper on June 10, 2008:

For more than a century, Indian Residential Schools separated over 150,000 Aboriginal children from their families and communities. In the 1870s, the federal government, partly in order to meet its obligation to educate Aboriginal children, began to play a role in the development and administration of these schools. Two primary objectives of the Residential Schools system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives were based on the assumption Aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. Indeed, some sought, as it was infamously said, “to kill the Indian in the child.” Today, we recognise that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country.

One hundred and thirty-two federally-supported schools were located in every province and territory, except Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Most schools were operated as “joint ventures” with Anglican, Catholic, Presbyterian or United Churches. The Government of Canada built an educational system in which very young children were often forcibly removed from their homes, often taken far from their communities. Many were inadequately fed, clothed and housed. All were deprived of the care and nurturing of their parents, grandparents and communities. First Nations, Inuit and Métis languages and cultural practices were prohibited in these schools. Tragically, some of these children died while attending residential schools and others never returned home.

…

To the approximately 80,000 living former students, and all family members and communities, the Government of Canada now recognises that it was wrong to forcibly remove children from their homes and we apologise for having done this. We now recognise that it was wrong to separate children from rich and vibrant cultures and traditions that it created a void in many lives and communities, and we apologise for having done this. We now recognise that, in separating children from their families, we undermined the ability of many to adequately parent their own children and sowed the seeds for generations to follow, and we apologise for having done this. We now recognise that, far too often, these institutions gave rise to abuse or neglect and were inadequately controlled, and we apologise for failing to protect you. Not only did you suffer these abuses as children, but as you became parents, you were powerless to protect your own children from suffering the same experience, and for this we are sorry.

The burden of this experience has been on your shoulders for far too long. The burden is properly ours as a Government, and as a country. There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the Indian Residential Schools system to ever prevail again. You have been working on recovering from this experience for a long time and in a very real sense, we are now joining you on this journey. The Government of Canada sincerely apologises and asks the forgiveness of the Aboriginal peoples of this country for failing them so profoundly.

…

The official apology acknowledges the fate foreseen by the two prominent chiefs who did not sign Treaty Six: Mistahi-maskwa (called Big Bear in English) and Pihtokahanapiwiyin (known to the colonisers as Poundmaker). Each thought the promises made to their people under treaty would not go far enough to protect their heritage, their ability to be and to belong.

Pihtokahanapiwiyin and Mistahi-maskwa were persecuted by the Canadian government as traitors after the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Mistahi-maskwa tried to stop his followers from attacking a settlement at Frog Lake, but was convicted by Canadian courts for the death of nine colonists that became known as the “Frog Lake massacre” in colonial history.

Pihtokahanapiwiyin in fact renounced violence, a fact finally acknowledged by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on 23 May 2019: “In 2019, we recognise the truth in his words that he — as a leader, statesman and peacemaker — did everything he could to ensure that lives were not needlessly lost. It has taken us 134 years to reach today’s milestone — the exoneration of Chief Poundmaker.”

…

And yet, from the ashes of betrayal and deracination, new leadership arises. We learn from the leadership of Autumn Peltier that wisdom is not confined to elders. As an 11-year-old she met with Justin Trudeau, and elicited from him a tearful promise that he would indeed ensure safe water for indigenous Canadians. The Trudeau government allocated billions of dollars to do so, but the money set aside is slow to be delivered, and in early 2019 there is little to show as tangible progress in terms of building the modern sewage and water treatment that would bring First Nations communities the civic infrastructure that prevails across Canada.

Autumn’s great-aunt was Water Walker Josephine Mandamin, who walked around all of the Great Lakes, and the entire length of the St. Lawrence River, starting in 2003. Autumn inherited her mantle. Aged eight, she participated in a water ceremony at Serpent River First Nation. As she described it at a mid-February 2019 meeting of Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) Oshkaatisak Youth Council gathering in Thunder Bay:

“I noticed there were signs on the walls that said: ‘Don’t drink this water, not for consumption, it’s toxic’. I asked my mom, ‘what does that mean?’ and she told me they were on a boil water advisory — they can’t drink their water. So after hearing that it became one of my biggest concerns, so I started public speaking about it.”

Her advocacy did not go unnoticed. Aged 13, Autumn was invited to address the United Nations General Assembly on World Water Day, March 22, 2018. She wore the mantle of leadership with a natural comfort, a girl barely into her teens, standing up before the assembled delegates of the world. And her words carried the clarity of uncompromised and undiluted belief: “Our water deserves to be treated as human with human rights. We need to acknowledge our waters with personhood so we can protect our waters.”

The notion of giving one of the elements essential to all life on earth the role of a person, is indeed a wrenching shift in thinking. Autumn and other keepers of the water know they have to care for this life-giving force because the adult world hasn’t. Autumn’s courage in speaking truth to power is a living example of satyagraha.

Her advocacy includes a guide for others who wish to become guardians of water. After her UN speech, she set out the path in an interview with CBC News:

➢ Learn as much as you can from your elders and your teachers.

➢ Learn your history. Learn your language. Listen and ask questions.

➢ Pay attention to the climate and the animals. Have respect for all living things.

➢ Talk with Mother Earth, sit with her and thank her. Make offerings of tobacco, pray and give thanks.

➢ Have fun and be a kid as much as you can. Get your school or class involved in a type of activity to help the land.

➢ Talk to your friends and share ideas. Inspire and encourage others.

➢ If you have an idea, act and make it happen. Don’t be shy, there are no rights or wrongs — anyone can do this work.

➢ Just do it!!!

The way Autumn and her generation perceive and approach Canada’s cultural genocide of indigenous communities is so strikingly different from the skein of prejudices which prompted residential schools — prejudices which persist in an adult population conditioned and shaped to regard indigenous Canadians as the Other. The classical perspective of a colonising population that has displaced the original inhabitants of the land is giving way to a new worldview, empowered by truth-telling and shaped by pluralism.

The children of Autumn’s generation are the first batch of schoolchildren to come to grips with the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: the catalogue of pain Chief Littlechild brought to our circle. In a Grade 9 classroom in south-east Edmonton, a raucous, passionate, occasionally insightful band of 14- and 15-year-olds come face to face with truth long suppressed. They are a diverse classroom typical of today’s urban Canada. They are first- and second-generation immigrants, the descendants of settlers from long ago and of the original people of Turtle Island. Their ethnic origins include Punjabi and Filipino, Somali and Colombian, Jamaican and German, Albanian and Canadian, Métis and Cree.

Many of them are being raised by single parents, adoptive parents, step-parents, and grandparents. They all face challenges, including those brought on by the pervasive violence of poverty, but these young people know that they are safe at school and that they have adults in their lives who love them fiercely. Today, they are uncharacteristically quiet. They are reading about residential school experiences, collected by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and told in the survivors’ own words.

This is what the children have to say in response.

“What happened to these kids shouldn’t have started in the first place. I see no reason as to why they treated kids that way just to assimilate them and make them act like white people. I hope the nuns and people who ran the school at least felt sorry after the schools shut down.”

***

“It’s ironic that the nuns and priests beat them to the extremes when they were supposed to be people of ‘God’. Why were they strapped for playing and talking? Expecting a child not to be a child is impossible.”

***

“Kids were severely punished for stupid reasons like talking, going pee at night, laughing, playing, and talking in their language. I knew kids were getting beat but I didn’t know what the reasons were until now. When I first learned about these schools I was curious about them, and now that I know more I feel absolutely sickened by how no one stood up for these kids at the start. Just thinking about it makes me want to go back in time and give those teachers a piece of my mind.”

***

“People shouldn’t be forcibly separated from your loved ones, especially if they’re properly caring for you. … Being beaten won’t change a person, it only builds up anger and hatred, especially for something like wanting to keep your language and culture when your roots are all you have.”

***

“The nuns beating kids challenged my thinking because nuns are supposed to be like helpful loving people. I could never imagine being whipped by some random person when my parents don’t even hit me, the most they do is yell at me.”

***

“If I was in this position I would feel so helpless and lost and upset. I would probably try to run away, too.”

***

“I assumed that these kids would at least have some freedom but it turns out every minute was monitored. I felt surprised and sad that these schools treated kids with neglect and fear and pain so they could control and change them. The public didn’t even know about this for the longest time and the public just assumed that the schools was a safe space for these children when in reality they’re getting abused.”

***

“I thought these people were messed up but still had some shred of humanity, but my thinking changed after reading this. I felt disappointed that the people doing these things could have quite possibly been my ancestors. I feel empathy for those who survived and realise how much I’ve taken for granted.”

***

“I knew the people working there would say ruthless things to the kids, but my perspective changed when I found out the kids would say such bad things about their own race and language. They felt being Aboriginal was a bad thing and felt ashamed for their families and the skin they had. I feel honestly disgusted by how they treated the children and if I were in their position, I would feel so upset and terrible.”

***

“I felt understanding when they expressed their pain and anger and how small they felt. After reading these experiences from other people, I realise how lucky I am. It really makes you wonder how the government thought they were in the right to send kids to these schools that were 90% abuse.”

***

“I believe that the First Nations were scammed and tortured for nothing but selfish and stupid reasons. The Europeans could’ve shown what they wanted in different ways that didn’t involve torture and harm to others. No one deserved to go through that torture. What they did goes against human rights, and just isn’t human in general.”

***

“What I took to heart was the amount of children who hated themselves and their parents and that is really sad because they didn’t get to live their lives like we do. Their whole lives got affected. … I would go back and make a difference if I could.”

***

“How can you learn to love or care about others when you don’t know how to love yourself? When you’re used to being treated badly you think it’s okay, but it’s not.”

***

“I was surprised by how little the government cared about these kids and how they didn’t see that they were humans too. Reading this gave me more respect for First Nations and helped me understand the impact residential schools have had on First Nations today. I feel that this is the most racist thing Canada has done and hope that people see that white supremacy holds humans back as a species to this day.”

***

“They took their lands, language, rights, children… I feel an immense amount of sadness because I cannot even imagine going through this. I don’t know how people could be so cruel.”

After these insights from a group of junior high school students learning about residential schools and exploring reconciliation, I can only add: Children, teach your parents well.

Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan May 2019

I am seated at my kitchen table with George Stanley and his brother Ernest. And although I do not know it, this is the day I am about to cross a threshold of trust and intimacy which is so deeply meaningful that it warms me to my core.

George is the fifth generation of hereditary chiefs in the Frog Lake First Nation. The hereditary system gave way to elections, but the heredity still carries an obligation to service. George calls me his brother, and enlists my support in seeking for his people all the benefits of modern life enjoyed by other Canadians. George has been an elected chief for his nation and a regional chief for Alberta in the Assembly of First Nations. He is the seventh of nine children and the youngest among the boys, yet his grandfather marked him as the hereditary chief: because the youngest sibling, not the oldest, is the one formed to lead.

George remembers sitting around the family dinner table before he was 10, when his father, Chief Jean-Baptiste Stanley, told him he would one day be the hereditary chief of his people: and schooled him thereafter in the art of leadership. George is my age. Luckily, he was spared the gauntlet of residential school education. His mother, Mary, was not so fortunate. She was torn away from her family on the Onion Lake First Nation when she was five, and did not return home until she had completed Grade Nine. George remembers the hole between the bones in the forefinger where she was injured in a teacher’s beating, the fracture never properly set or healed.

Today at my table, George seated in his familiar place, looking out the French doors to the garden, we are joined by George’s elder brother, Ernest. Ernie, as the family knows him, has met me perhaps a half a dozen times. And said very little. George is the voluble one, the born politician. Ernie has always been reserved, keeping his thoughts and emotions to himself. There has been a time or two when George — his mobile phone gone awry — uses his siblings’ phones instead, so I am used to calls from numbers I do not recognise. The most Ernie has ever said to me, when I answer the phone is, “This is Ernie. Your brother wants to talk to you,” as he passes George the phone.

Ernie is the bundle holder, the keeper of the sacred relic that validates and sanctifies Treaty Six. Today, at my kitchen table, George tells me that Ernie has something to say. Ernie produces a filter tipped cigarette. The gift of tobacco. He asks me to place it at the base of a tree. I step outside into the yard, break the cigarette apart, and place the blessed tobacco in a little hollow I carve at the roots of our rhododendron.

Then Ernie speaks. I listen, rapt, for ten minutes as he articulates a profound emotion, not daring to interrupt. He and his fellow elders are deeply concerned by the corruption they perceive in the government-sanctioned elections on their nation. They have come through a recent exercise where candidates distributed ballots, and recounts that changed the results were held with only half the scrutineers present.

“We respect the Indian Act, the laws of the Crown,” Ernie says, “because we have followed it for so many years. I want to make that clear. But for many years now, we have seen how the laws of the Crown lead to corruption. This time, we elders want to step in. We have been the guardians of our people. Before elections, we were the ones responsible to make sure our people were wisely led. But now, we have to step in. The Crown laws bring us leaders who are corrupt. We have to keep the trust of the people.”

Ernie asks my help as a scribe in gathering his thoughts into a letter he and his fellow Elders will send to Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. And invites me to a sacred gathering to share a pipe with the elders to commemorate treaty, where the bundle may be opened for the first time in many years.

I am still coming to grips with what Ernie has just said, the blessing he has conferred on me and my family with the gift of tobacco, the door he has opened as keeper of the Treaty Six bundle. This is the moment I go beyond my passport identity, my legal status of citizenship, to become fully and wholly Canadian: a child of kisemanito’s bounty, at last in the full embrace of the first peoples who welcomed newcomers to this land.

The corruption Ernie speaks of, George’s continuing efforts to secure clean water and proper sanitation for his nation, are part of the failures for which Canada must atone.

At the bookends of generations, Autumn and George are leading the same human right: the right to clean water. Very much a part of the right to health, and to the security of the person. George, the veteran politician. Autumn, the vanguard of the children who will cope with the toxic legacy we are leaving them.

Frog Lake First Nation has its very own oil company, but the community itself has open sewage lagoons between the high school and the hospital. The government of Canada, which has overarching control of infrastructure on reserves, has determined that these lagoons are the most cost-efficient way of treating cess and effluents. The civil servants who designed and emplaced these cesspits do not have to live next to them.

Safe water, a given for nearly every Canadian living off-reserve in a municipality, is denied to thousands of Indigenous people. In April 2019, there were 57 Indigenous communities where residents were asked to boil water before consuming it. The Government of Canada aims to provide safe water to all affected communities by 2021.

For George, this is just another deferred promise: a pattern of the broken or unfulfilled commitments made by the politicians of the Crown, only to be thwarted in execution and delivery by the structure of governance.

As George and I engage in meaningful conversation week by week, we wonder where we have gone wrong: at the end of the day, we as leaders, we as a country, have failed utterly to provide the basics of a clement life to indigenous Canadians. And we know that we cannot look Autumn in the eye without feeling a measure of failure and shame. We are passing her the torch, yet the light is anything but pure and bright.

Which is why we Canadians cannot even afford a hint of smugness or sanctimony as we lecture others on human rights. Until we have atoned for the never-ending sin, until we have fulfilled the birthright of indigenous Canadians to live a life of meaning and purpose in the full expression of human dignity, with freedom from fear and freedom from want, we have no lesson to teach anyone.

If we are all people of Treaty, if we are all the fruit of the creation animated by kisemanito, why do we find it so hard to ensure that all Canadians enjoy clean water, clean air, and life-bearing land?

The answer lies, perhaps, in what Gandhi taught. Our continuing journey through the story of Us brings an understanding that we must each, in our own way, become the change we want to see. And find our own path, our own way of being and becoming, as we pursue a better world than the one we inherited.

satya@cambridgestrategies.com